Klasični razgovori sa umetnicima.

Perspektive umetnika: priče iza nota. Razgovori o nadahnuću, stvaranju i umetničkim putevima.

Alexander Liebermann: Music is my primary means of self-expression

In this exclusive interview, his first for the Serbian-speaking audience, composer Alexander Liebermann talks about his creative process, fascination with birdsong, and the connection between music and science. Discover how he blends nature and art to create his unique musical world.

Interview with a composer Alexander Liebermann

Verzija intervjua sa kompozitorom Aleksandrom Libermanom na srpskom jeziku nalazi se na ovom linku.

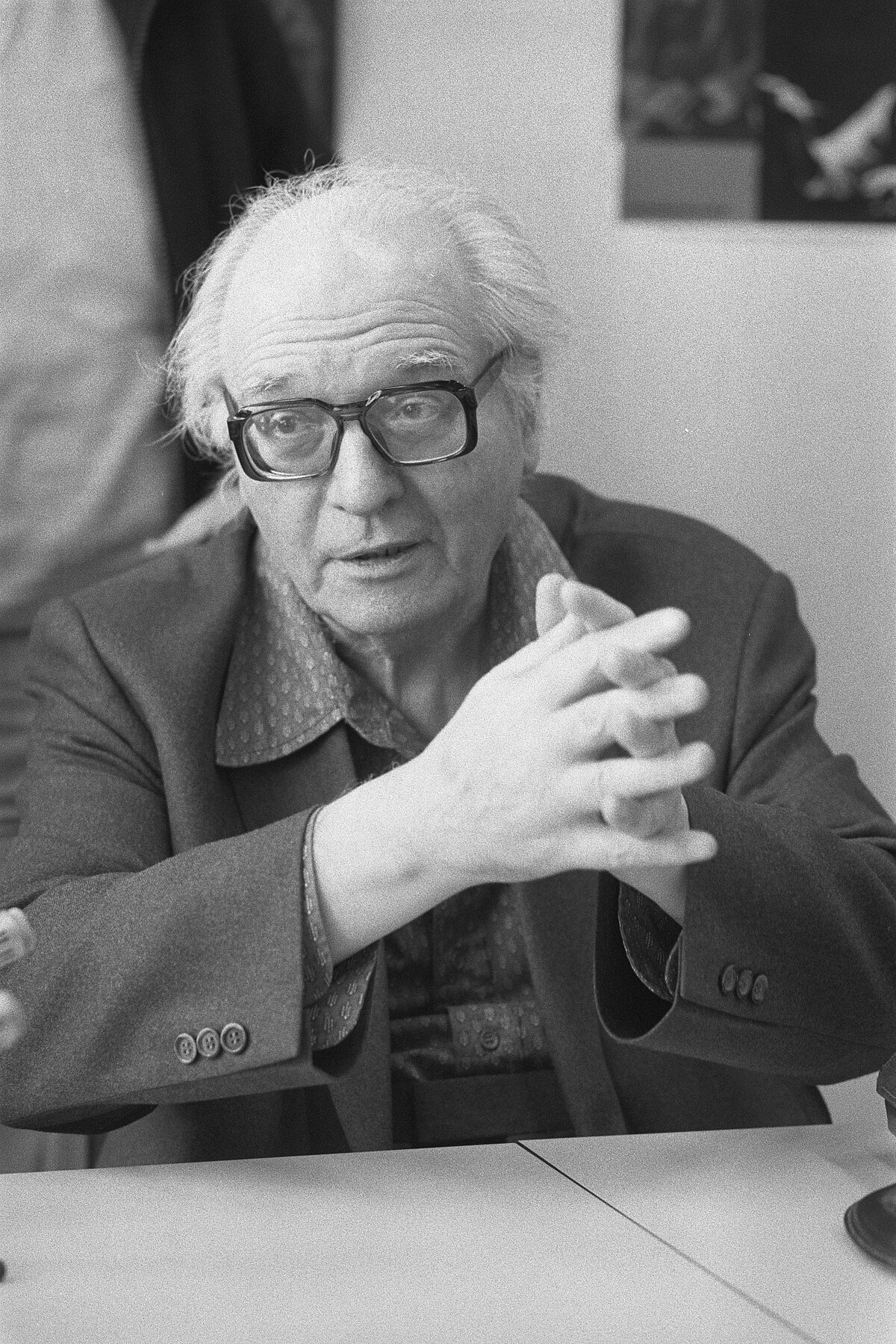

Alexander Liebermann, composer

Photo: alexanderliebermann.com

I first discovered Alexander Liebermann in 2022, thanks to The Best Classical Music Podcast. What immediately caught my attention about this incredible artist was his passion for animal songs, particularly bird songs. I vividly remember listening to him speak about music, his transcriptions, and the challenges he faces while transcribing, all during a bus ride between my hometown and the city where I live.

As a nature enthusiast, especially fond of birdsong—a love I inherited from another bird admirer, Messiaen—I was inspired to delve deeper into Liebermann’s music. I started exploring his work on YouTube and following him on social media. Nearly every week, he would share a transcription accompanied by an explanation of the unique melodies birds produce, and I’ve been captivated ever since.

When I launched my blog a few months ago, I knew I had to interview this extraordinary artist. I felt a strong desire to introduce his work to my friends and colleagues in Serbia. And so, here it is—my small contribution to spreading the word about the remarkable Alexander Liebermann.

It is known that you began transcribing bird songs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recordings sparked your curiosity about animals and the sounds they produce. What challenges do you encounter when transcribing animal songs, and what fascinates you to continue exploring this field?

That's right. After spending a week in the Costa Rican nature, the Pandemic hit, and I found myself back in my childhood room in Berlin. Suddenly, I realized what incredible things I had witnessed (and more importantly, heard!) in that nature. That’s when I began to google the birds I had seen and to transcribe their songs.

What fascinates me about animal songs—particularly those of birds—is their astonishing complexity. When you attempt to transcribe their vocalizations into musical notation, you realize how intricate and complex they are. You are essentially listening to the culmination of millions of years of evolutionary refinement, and that’s both humbling and awe-inspiring.

Music is my primary means of self-expression

〰️

Music is my primary means of self-expression 〰️

You often mention that the musical notation we use for composing has many limitations when it comes to transcribing animal songs. What have you discovered during your transcription work that is specific to animal songs yet difficult or nearly impossible to represent in classical notation?

Of course, our current system of musical notation has its limitations. The Western system is remarkably precise and continues to evolve with each new generation of composers (Think about George Crumb's notation of the 'seagull effect'), but it may never fully capture the complexities of all birdsongs.

Nightingales, for example, are extremely challenging to transcribe. Their vocalizations have clear-pitched whistles, various non-pitched sounds, and lots of very clear overtones (and all of that happening outside the framework of our 12-tone system). This makes an accurate transcription nearly impossible to do.

Evoking Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Messiaen: Composer of Sound and Color

Olivier Messiaen is perhaps the most famous composer for his journeys to tropical forests to listen to and transcribe the songs of various exotic birds. There is a wonderful documentary about him and his work called The Crystal Liturgy. Could you share what is unique about Messiaen’s transcriptions of bird songs? How does your approach differ from his, or are there similarities?

Messiaen is one of my favorite composers. I’m bummed because I was only three years old when he passed, and a part of me still feels there could have been a chance for me to meet him. I love his music, and I've spent time studying his transcriptions of birdsong, comparing them to those created by others, such as Hollis Taylor.

One thing that really struck me is the difference between how a composer transcribes birdsong versus how a musicologist/zoomusicologist approaches it. Messiaen, for example, seems to have transcribed through the lens of a composer, listening to the birds musically and imagining how their songs could be performed or integrated into his work. While that perspective is perhaps inevitable for composers, I try to approach transcription a bit differently by notating every single detail I can hear—and thus not worrying about whether it’s performable or not. Of course, having tools and software that allow me to slow down recordings has been a great help.

Messiaen believed that humans learned to sing and make music from birds. Does this idea make sense to you? Do you think nature has awakened humanity’s interest in music?

All I can say to that is that the etymology of the word composing comes from the Latin word ‘componere’, meaning "to put together." At its core, I believe everything is imitation. And through imitation, we develop and evolve.

Our species first appeared around 200,000 years ago, and some of the oldest known instruments are more than 35,000-year-old (like the five-finger flute made of bone discovered in what is now Germany). In the grand timeline of nature, this is but the blink of an eye ago. The sounds of birds and other animals from back then were likely quite similar, and certainly more abundant. Now imagine hearing a cuckoo—wouldn't you feel compelled to imitate it? I still respond to owls, imitating them whenever I hear them on summer nights. So, yes, it makes perfect sense that, in the beginning, we imitated the sounds (pitches and rhythms) that nature offered us.

Quaraçá for Wind Quintet is inspired by the song of the Uirapuru, a South American bird native to the Amazon rainforest.

The Birds’ Hidden Language

What have you learned or discovered so far about animal songs? What secrets do they hold? Are there any similarities between their music-making and human music?

I am still quite new to this field, but I have learned a great deal through reading and collaborating with scientists (primarily biologists and ornithologists). Books like The Bird Way by Jennifer Ackerman and Nightingales in Berlin by David Rothenberg have taught me not only about birds but also about the parallels with human music-making. Did you know that zebra finches learn their songs by memorizing and practicing? And male nightingales produce a specific sound that females find “sexy.”

In my work transcribing birdsong, I’ve discovered that the possibilities of pitch and rhythmic combinations are virtually infinite. In the songs of nightingales, I’ve encountered jazz-like licks and pitch sequences reminiscent of famous musical themes. On the other hand, blackbirds and Blyth’s reed warblers sing almost perfect triads and seventh chords. It’s truly amazing when you think about it.

What fascinates me about animal songs—particularly those of birds—is their astonishing complexity.

Your body of work includes a significant number of compositions. Listening to them and trying to identify your unique musical expression, I noticed that your music often feels picturesque, descriptive, and inspired by representations of the world and nature. How do you overcome the limitations of instruments in your compositions when trying to imitate the natural phenomena that inspire you?

That’s a great question, and it’s something I’m still grappling with. I tend to be a bit conservative when it comes to orchestration and melody. However, the sounds created by birds (and other animals) can be so ethereal that they demand new instruments and a completely different approach to orchestration. It’s a real struggle for me because I want to be able to imitate or recreate these sounds using a more traditional orchestra.

In a recent piece I composed, I implemented the call of a red-tailed hawk into the orchestral texture. The call sounds like white noise, but I think I managed to imitate it quite well using the traditional orchestra. Keep it between us, but it involved high string harmonics in a dense cluster, along with an incredibly high piccolo flute.

Music and nature

Liebermann’s compositional oeuvre spans dozens of works for various instruments and ensembles. From solo music and choral pieces to chamber and orchestral works, his versatility as a composer is remarkable. Notably, he also composed music for the film Frozen Corpses Golden Treasures.

A defining feature of Liebermann’s music is his integration of bird songs into many of his compositions. However, his work extends beyond this, as he is deeply committed to exploring the connection between music and science. A standout example is a piece that emerged from his collaboration with biologist Professor C. Loren Buck from Northern Arizona University. Together, they aimed to musically represent the annual cycle of Arctic ground squirrels—extraordinary creatures that hibernate for over half a year with body temperatures dropping below freezing. Through this composition, they sought to capture the essence of the squirrels’ existence while drawing attention to the growing threats these animals face due to global climate change.

I believe that making music an interdisciplinary field is crucial for the 21st century.

You are of French and German origin, yet you have been living and working in the United States for quite some. Could you describe how American musical traditions have influenced your compositional style compared to European traditions? Are there distinctions, and how do they relate to your work?

I studied at the Music University “Hanns Eisler” in Berlin, majoring in music theory and jazz composition. While I aspired to write “serious” music like the composers in the contemporary composition division, I didn’t want to follow the experimental and "Neue Musik" style that dominated the scene. Feeling out of place, I decided to leave for the US to study with Samuel Adler and Steven Stucky at Juilliard. There, I noticed that the musical language of all the students was eclectic (in the good sense of the word!), and that was truly refreshing to me.

In Germany, I felt that writing melodies was not considered a serious way of composing. While that may not be the case anymore, at the time it certainly felt that way. Melodies are important to me, and they are never entirely absent from my compositions. I often reference Messiaen’s words on this subject. In 1944, he wrote about his own musical aesthetic:

“With the awareness that music is a language, we will first strive to let the melody ‘speak.’ The melody is the starting point. It must remain sovereign! […].”

That said, I also have a deep appreciation for atmospheric and ambient music, and in recent years I’m finding myself more and more drawn to experimental music. Let’s see where this takes me.

Melody and noise

What does music, and your compositions in particular, mean to you considering the inspirations that drive your creative process?

Music is my primary means of self-expression. However, as a naturally curious person, I also use it as a tool to explore various subjects. While I certainly write pieces inspired by birds, I’ve also composed about topics such as climate change, history, and other animals like arctic ground squirrels. For the latter, I collaborated with scientist C. Loren Buck, using his data to shape the form of the piece. I believe that making music an interdisciplinary field is crucial for the 21st century—it can not only reach a broader audience that way but also serve as an effective educational tool.

Considering that music can be “captured” from everything around us, how can we distinguish between melody and noise?

Ha-ha! That’s a tricky question. First, melody is not the opposite of noise. A "melody" (and define melody) could be considered "noise" by some. And then, what exactly is music? I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on this over the years, and the truth is, there’s no single, universally accepted definition. (For fun, try looking up the definition of music in different countries!)

However, there are two definitions that resonate with me. The first is a more philosophical and pragmatic definition by Andrew Kania:

“Music is (1) any event intentionally produced or organized (2) to be heard, and (3) either (a) to have some basic musical feature, such as pitch or rhythm, or (b) to be listened to for such features.”

And then there is the more “romantic” one, as given by David Rothenberg:

“Before music, sound is sound. After music, sound is still sound, but our feet are walking a few inches above the ground.”

Ultimately, I believe it’s up to the listener to decide what qualifies as music, and therefore to distinguish between melody and noise. To me, both melody and noise are integral parts of what music is.

Birdsong: A Musical Field Guide

Another fascinating aspect of Liebermann’s work is his book Birdsong: A Musical Field Guide.

This book is a treasure for both musicians and nature enthusiasts, featuring highly accurate transcriptions of birdsong. It includes beautiful illustrations of each bird species, created by artist Anna Schiller, along with QR codes that link directly to the original videos. This allows readers to listen to each bird’s song while following the music, creating an immersive and educational experience.

Erwin Schulhoff – A Composer of Many Faces

Your doctoral dissertation focuses on the Austro-Czech composer and pianist Erwin Schulhoff. What drew you to research Erwin Schulhoff, and what unique aspects have you discovered in his compositions?

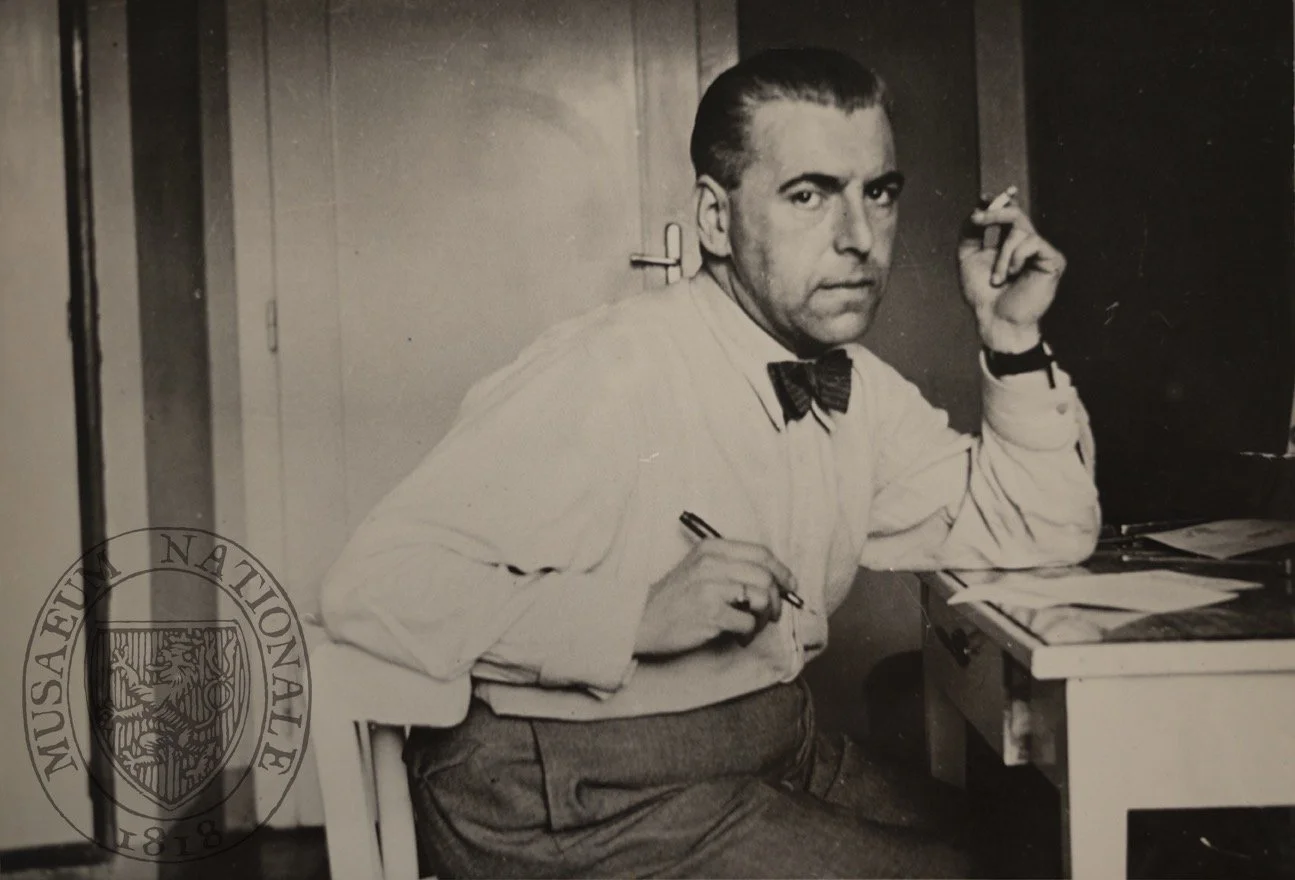

Erwin Schulhoff, composer

He was passionate about all kinds of music, exploring Post-Romanticism, Dadaism, French and German Expressionism, and even jazz!

I absolutely love Schulhoff’s music. Not only is the music from his string sextet one of my earliest musical memories, but I also feel a deep connection to him. Let me explain. First, Schulhoff was German-Czech and grew up with the internal dichotomy of not quite knowing where he belonged. This is something I can relate, with my own French-German roots.

Secondly, Schulhoff lived during a time when genres and musical styles were exploding. He was passionate about all kinds of music, exploring Post-Romanticism, Dadaism, French and German Expressionism, and even jazz! It must have been overwhelming to live through such a transformative time. Schulhoff embraced many of these styles and eventually succeeded in creating his own unique musical language by assimilating elements from the ones he liked most.

Today, we face a similar situation. We are surrounded by so much music, and we can listen to everything, everywhere, all at once. I love Debussy and Ravel, but I also have a passion for J.J. Cale and even AC/DC. The list is endless. So why wouldn’t I incorporate uplifting beats into my music, or a power chord here and there? I’m still working through this, but Schulhoff is a huge influence and inspiration in that regard. That’s why I wrote my doctoral thesis on his music.

Which part of his oeuvre do you consider the most innovative, and why?

To be honest, I don’t know if his work is that innovative, and that’s perfectly okay. What matters most is that whatever he wrote, he wrote well—really well! It is good music and I listen to it frequently. What more could a composer wish for than to have the next generation of musicians and composers listen to and be inspired by their work?

That said, if there is one piece that is truly groundbreaking, it is probably the Five Pittoresques from 1919. It is one of the first classical compositions to incorporate jazz elements throughout (with only Stravinsky’s Piano Rag beating Schulhoff by a couple of months). Additionally, the piece features a movement made entirely of silence, and that 33 years before John Cage’s 4'33!

Please check out his music. For starters, I recommend the Hot sonata, the String Sextet, and his Five Pieces for String Quartet.

Alexander Liebermann, in a few words

Alexander Liebermann is a German-French composer of classical music, whose acclaimed works are characterized by an eclectic blend of diverse topics such as philosophy, biology, astronomy, and other fields. Among his most recent commissions are a climate-change-reflecting monodrama written for the Deutsche Oper Berlin, a birdsong-inspired wind quintet for the Brazilian Winds Ensemble, and a soundtrack for the documentary film Frozen Corpses Golden Treasures.

As a passionate nature enthusiast, Liebermann spends much of his time studying the sounds of wildlife. He is known for his original and accurate transcriptions of animal vocalizations, which have gone viral on social media and been featured in the world-renowned magazine National Geographic. These transcriptions have also earned him invitations to international congresses in Colombia and Brazil, as well as a feature on CBS Sunday Morning. Liebermann is the author of Birdsong: A Musical Field Guide, a book that offers a unique perspective on the musicality of birds and their relationship to human music-making.

Liebermann holds degrees from the Hanns Eisler Music Conservatory, the Juilliard School, and Manhattan School of Music. For his thesis on Erwin Schulhoff, Liebermann was awarded the Saul Braverman Award in Music Theory. Liebermann currently resides in New York and serves as a faculty member for music theory and ear training at Juilliard’s preparatory division Music Advancement Program.

Mina Gligorić: Postajemo svetlost kada zagrlimo svoj mrak

Razgovor sa operskom umetnicom Minom Gligorić usledio je nakon premijere Rubinštajnove opere Demon u Srpskom narodnom pozorištu, gde je Mina tumačila ulogu Tamare. Njen pristup ulozi, obogaćen filozofskim, dramaturškim i psihološkim promišljanjima, otkrio je dublji sloj ove kompleksne opere.

Intervju sa operskom umetnicom Minom Gligorić

Mina Gligorić, operska umetnica

Fotografija: Vesna Anđić

Razgovor sa operskom umetnicom Minom Gligorić odigrao se ubrzo nakon premijere opere Demon Antona Rubinštajna u Srpskom narodnom pozorištu u Novom Sadu. Mina je pevala ulogu Tamare, glavne junakinje koja se u operi suočava sa borbom između svetlosti i tame, oličene u liku Demona koji pokušava da zavlada njenom dušom. Pristupivši liku Tamare ne samo kao muzičkoj ulozi, već i kroz prizmu filozofije, dramaturgije, psihologije i duha vremena u kojem je opera nastala, Mina je pokazala duboko promišljanje ne samo o ovom liku već i o celokupnoj produkciji opere. Sama sebi postavljala je pitanja o prirodi Tamarinog odnosa sa Demonom, njegovom uticaju na njen život, njenom mestu u društvu i njenom psihološkom stanju.

U ovom razgovoru nastojao sam da zabeležim sva ta Minina razmišljanja i da ih prenesem svima vama koji ćete pročitati ovaj intervju.

Kako te je inspirisao lik Tamare u procesu pripreme same uloge? Kako si je videla, doživela i kako si je interpretirala na sceni?

Uloga Tamare je kompleksna, pre svega zbog njene dramaturgije. Prvi put sam se susrela s njom u februaru mesecu ove godine, na poziv Srpskog narodnog pozorišta da budem deo projekta, a već sam paralelno istraživala tamne strane ljudske prirode i motiv senke u operskoj literaturi, kao i književnim delima. Fascinirao me je njen unutrašnji sukob između tame i svetlosti, kao i transformacija mlade devojke iz nevinosti, zatvorene u okruženju svojih drugarica i oca. Kao knjeginjica, ona je na visokom položaju, ali bez pravog kontakta sa spoljnim svetom, osim očekivane udaje, iako joj je princ Sinodal simpatija od detinjstva.

Privukla me je njena senka, koje nije svesna, a koja predstavlja strahove i društveno neprihvatljive aspekte svakog od nas. Kada prvi put čuje Demona, Tamara posmatra svoja osećanja radoznalo, ali kasnije počinje da ih se plaši kada shvati šta to sve znači. On joj obećava da će biti carica sveta i samo njegova, a taj koncept posedovanja je zastrašujuć. Kulminacija njenog verovanja dolazi sa smrću budućeg verenika. Ovaj ples između tamne i svetle strane je ono što me je najviše inspirisalo u interpretaciji njenog lika.

A u dramaturškom smislu?

U dramaturškom smislu, Rubinštajn je konstruisao prvi čin tako da je moj zadatak kao umetnice bio da prenesem transformaciju od vesele devojke, koja peva u koloraturama i melizmima i zrači životnom energijom, do očaja u drugom činu, gde se Tamara suočava s iskušenjem koje je demon sve vreme uvlači.

Kako gledaš kroz Tamaru na pojam romantičarske lepote?

Romantičarske lepotice se, za razliku od onih putenih figura realizma, odlikuju duhovnošću i savršenstvom, kao da su blizu nekog božanstva. Međutim, nad njima često visi senka tame, jer su romantičarski pisci počeli da humanizuju demonska bića, podižući svest o tome da u svima nama koegzistiraju i svetlost i tama. One su često bile meta demonima zbog svoje čistoće.

Postajemo svetlost kada zagrlimo svoj mrak

〰️

Postajemo svetlost kada zagrlimo svoj mrak 〰️

Romantičarske lepotice se, za razliku od onih putenih figura realizma, odlikuju duhovnošću i savršenstvom, kao da su blizu nekog božanstva.

Fotografija: Vesna Anđić

Kako shvatiti Tamarinu borbu s mračnim silama?

Tamarina borba može se preneti u današnji svet: postajemo svetlost kada zagrlimo mrak, jer bez mraka ne možemo istinski svetleti. Imamo slobodu izbora da li ćemo svetleti ili ne, a svetlost dolazi kada, uprkos mraku, ostajemo slobodni u svom biću. Demon nije mogao da postigne ovu slobodu jer je bio zakovan sopstvenim bićem i želeo je da uzme Tamarinu svetlost, jer je u sebi nije mogao pronaći.

Smatrao je da će ga neko drugi spasiti, pa je zbog toga tu svetlost hteo da uzme od nje. Tamara, kao mlada devojka, morala je da iskusi mrak, ali ju je anđeo spasio. Iako je Demon uspeo da je ubije svojim poljupcem, njemu je bila potrebna njena duša. Međutim, ona je dobila pomoć Boga i anđela jer je, u suštini, bila čista i bez loših namera. Uzbuđenje koje je doživela bilo je novo iskustvo, a to se povezuje s romantizmom, gde čovek postaje živ tek kroz najuzbudljivija osećanja. I Tamara i Demon suočavaju se s tim osećanjima, ali svako to rešava na svoj način. Tamara želi da pomogne Demonu i ostaje na strani dobra, što je spašava, dok, na primer, Margareta iz opere Faust gubi svoju borbu. Tamara se borila do poslednjeg trenutka.

Kako se Tamara i Demon bore sa zatvorenošću? Da li možemo govoriti o dobru ili zlu?

Oboje su zatvoreni u svojim svetovima, ali ne bih rekla da je Tamara nesrećna u tom zatvoru. Ima oca i drugarice koji je vole i pružaju joj zaštitu. U svojoj poemi, Ljermontov opisuje Tamara kao strastveniju i drugačiju od svojih drugarica. Ona je nesvesno strastvena i poletna, što me je navelo da je ne prikažem kao koketnu. S druge strane, Demon se bori sa svojom zatvorenošću i očajem.

Tamara možda ni ne zna šta je sloboda, jer je već u svom komforu iz kojeg ne mora da izlazi. Njihova glavna razlika leži u tome što Tamara nije upoznata s drugim osećanjima, dok je Demon spoznao strukture mraka. Iako je napustio Boga i iako je proklet, on ne želi da seje zlo; jednostavno želi da veruje u nešto drugo i da se spasi putem ljubavi.

“Tamara dobija epitet anđeoske gospe jer je njena čistoća put do Demonovog spasenja, pa čak ni smrt ne postaje nešto tragično već uzivšeno.”

Mene sve ovo što pričaš o Tamari podseća na epitet anđeoske gospe, odnosno arhetip romatničarske heroine…

Slažem se! Tamara dobija epitet anđeoske gospe jer svako od nas mora da prigrli i mračne i svetle delove svoje prirode. Čak ni smrt ne postaje tragična, već uzvišena. O tome su govorili Dante i Ruso, koji je definisao pojam “je ne sais quoi” — lepota koja prevazilazi ljupkost i prosvećenost, već postaje uzbuđenje koje se budi u duhu posmatrača. Romantizam teži da svetlost lepote osvetli i najmračnije delove života, čime se bavi i ova opera, naglašavajući da svako od nas mora da prigrli i svoje mračne i svetle aspekte.

Kako je izgledala tvoja priprema za lik Tamare?

Pre nego što sam prešla na vokalni deo, puno sam se bavila literaturom. Čitala sam Ljermontovljevu poemu u prevodu Jovana Jovanovića Zmaja i inspirisala se time što svaki lik u operi ima uticaja na moj lik i obrnuto. Pitala sam se ko je bio Demon, zašto je pao i istraživala teološke izvore koji se bave pitanjem njegove odbačenosti od Boga. Uključila sam i psihološku knjigu Romansa sa senkom, koja se bavi temom senke u operama i drugim delima poput Slike Dorijana Greja, Fausta i Fantoma iz opere, kao i Istoriju lepote Umberta Eka.

Analizirala sam i lik Demona kroz društvenu kritiku početka 19. veka, pri čemu su neki smatrali da se Ljermontov identifikovao s Demonovom sudbinom, jer je i sam bio odbačen. Pokušala sam da obuhvatim različite aspekte – psihološki, teološki i romantičarski.

Verujem da svaki umetnik treba da pronađe deo sebe u liku koji tumači. Tokom pripreme, istraživala sam tamne strane svoje ličnosti iz radoznalosti. Te psihološke knjige pomogle su mi da pronađem mir i svetlost i da prigrlim svoj mrak. Da bi publika poverovala umetniku, on mora istražiti sebe do kraja, a umetnost će ga lako dovesti do samospoznaje.

Kakva je sloboda kojoj Demon teži? Kako možemo shvatiti slobodu danas i nekada?

Tema slobode ostaje zanimljiva jer se filozofija vekovima bavi ovim pitanjem. Prosečan savremeni čovek obično shvata slobodu kao sposobnost da izrazi svoje mišljenje i da ne polaže račune nikome. Međutim, smatram da je taj odnos prema slobodi često bežanje od suštine. Za mene je sloboda povezana sa unutrašnjim bićem i vernošću samom sebi, a pravi koncept slobode zahteva prihvatanje svih naših mračnih strana. Sloboda je sinonim za istinu. Lažni identiteti koje preuzimamo u želji da se uklopimo često nisu u skladu sa potrebama duše. Prvi korak ka slobodi je ljubav i osluškivanje najistinskijih delova sebe.

Demonova potraga za slobodom kroz ljubav, koju je u početku odbacivao, vodi ga do stvarne slobode. Iako se vernost osećanjima često doživljava kao ograničenje slobode, zapravo, to nas čini živima. Romantičari su demistifikovali demone, humanizujući ih, što je bila i ideja reditelja opere. Demonovo insistiranje na slobodi odražava duboku potrebu da se oslobođeno srce suoči s vlastitim mračnim aspektima.

Verujem da svaki umetnik treba da pronađe deo sebe u liku koji tumači. Tokom pripreme, istraživala sam tamne strane svoje ličnosti iz radoznalosti.

Fotografija: Vesna Anđić

Kakva je to pobuna koju čovek danas može imati u kontekstu sistema u kojem živi?

Čovek i danas teži slobodi, ali često pogrešno razume njen koncept. Svi pričamo o slobodi, ali retko je istinski doživljavamo iznutra; prava sloboda nosi mir i pomirenje. Naš ego nas često koči, baš kao i Demona.

Reditelj je naglasio da Tamarin odlazak u manastir ne treba posmatrati kao fizički izlazak, već kao njen sopstveni zatvor koji je sama stvorila. Tamara se krivi što je okusila slobodu, koja je došla s žrtvom—smrću njenog supruga. Umesto da uživa u svojoj slobodi, odlučuje da se zatvori, odlučivši da će služiti društvu, ocu, kneževini i mužu. Kada je pokušala da pobegne u svoju slobodu, to joj se obilo o glavu, pa se svesno vraća u zatvor jer veruje da njena željena sloboda nije prihvatljiva. Kraj dela demantuje tu ideju, jer se njena duša, koja treba da ostane večna, ne predaje iskušenju. U odnosu na prolaznost, večnost ima veće vrednosti za anđela i Boga, dok Demon više ceni prolaznost. Ova suprotnost je veoma zanimljiva i duboko reflektuje ljudsku prirodu.

Okrenimo se malo muzici. Kako je muzički prikazan lik Tamare?

Muzički, lik Tamare se prikazuje kroz njen vokalni izraz, posebno u koloraturama prvog dela opere, koje odražavaju njenu čistost, nevinost i devojačku lepotu. Svaki trenutak u njenom pevanju oslikava radost i bezbrižnost, a orkestarska pratnja je suptilna i skromna, što dodatno naglašava njen lik. Hor u pozadini peva Zlatna pleše ribica, simbolizujući Tamaru kao ribicu koja plovi morem, puna života.

Prvi deo opere predstavlja odu mladosti, dok drugi deo prelazi u dramski ton. Ovde se javlja značajan raspon tonova, koji se kreće od visokih tonova do dubljih. Dubine njenog emocionalnog stanja se ne čuju u prvom delu; one se manifestuju kada izgovara reči poput sahranite me i više mi život nije mio. Ove fraze predstavljaju njen krik, a njeni tragični emotivni osećaji postavljaju izazov za soprane.

Melodijske linije u drugom delu su gušće, naročito u duetu sa Demonom, što dodatno povećava dramatičnost. U svojoj pripremi, trudila sam se da radim sa bojama u svom vokalnom aparatu, kako bih prešla od svetle boje šesnaestogodišnje devojčice do tamnije boje zrele devojke koja odlazi u manastir. Ovaj kontrast u tonovima pomaže da se prikaže Tamara kao kompleksan lik koji prolazi kroz duboka emotivna iskustva.

Kakva je bila saradnja sa asistentom reditelja?

Saradnja sa asistentom reditelja, Iljom Iljinom, bila je izuzetno inspirativna. On nam je pružio veliku slobodu u interpretaciji, što je omogućilo da svaka od nas, uključujući moju koleginicu Ljupku i mene, razvije svoj jedinstveni pristup liku Tamare. Svaka od nas je dolazila iz svoje istine i to je, mislim, veoma važno. Savetovala bih svakog pevača da krene iz svoje istine kako bi oblikovao lik; na taj način publika može da poveruje u ono što prikazujemo.

Režija nije bila fiksirana, što nam je omogućilo da istražujemo likove na različite načine. Moje glavno pitanje tokom pripreme bilo je da li Demon stvarno voli Tamaru, a Iljinova interpretacija je bila da Demon samo misli da je voli, jer neko ko nije rešio pitanja sopstvene tame ne može biti sposoban ni istinski da voli drugo biće.

Proces rada je bio veoma intenzivan; postavljao nam je različita filozofska pitanja koja su nam pomogla da dublje istražimo naše uloge. Osećali smo se veoma povezano kao tim, i to je doprinelo našem zajedničkom nastupu na sceni.

Kakva je bila saradnja sa dirigentom Željkom Milanović?

Saradnja sa dirigentom Željkom Milanovićem bila je izuzetno plodna. Prvo smo radile na istraživanju boja i tempa, što je bilo ključno za moju interpretaciju. Željka je imala poseban senzibilitet za muziku, i veoma sam joj zahvalna za divnu saradnju. Tempo je bio važan segment našeg rada; prilagodili smo ga tako da bude u skladu sa našim mentalitetom i temperamentom. Njena sposobnost da oseti i usmeri dinamiku na sceni doprinela je da svaki trenutak dobije dodatnu dubinu.

Mina Gligorić u ulozi Tamare u operi Demon Antona Rubinštajna.

Fotografija: Marija Erdelji

Sloboda kao motiv: tri uloge, tri priče

Učestvovala si u premijeri opere Koštana 2019. godine u Narodnom pozorištu pevajući ovu naslovnu ulogu. Šta je to u njenom liku što ti je bilo interesantno?

Za lik Koštane me vezuje jedna reč – sloboda. Ponovo se vraćamo pitanju slobode, ali u drugačijem kontekstu. Koštana je lepotica sa juga, temperamentnija je u odnosu na Tamaru. Ona predstavlja divlju prirodu koja čezne za slobodom koja joj je od samog početka oduzeta. Za razliku od Tamare, Koštana je mnogo više poznavala ljude i imala je iskustvo kroz svoje pevanje i društvene interakcije. Njena svest o slobodi i njena borba za nju oblikovane su njenim odrastanjem i životnim iskustvima, što je čini vrlo zanimljivim i složenim likom. Njen temperament i strast prema slobodi dodatno obogaćuju priču i čine je neodoljivom.

A u liku Kristin u Fantomu iz opere?

Kristin ima sličnu tematiku kao Tamara i Demon. Na početku, ona Fantoma samo čuje, baš kao što Tamara čuje Demona. Kristin je takođe vrlo mlada i obećana Raulu, svojoj divnoj mladalačkoj ljubavi. Međutim, osećanja koja Fantom budi kod nje su van njene kontrole.

Postoji značajna razlika između njih: Fantom je čovek koji je demonizovan, dok je Demon pali anđeo koji je humanizovan. Ova dinamika dodatno komplikuje Kristinina osećanja, jer se suočava sa unutrašnjim sukobom između svoje mladalačke ljubavi i misteriozne, mračne privlačnosti Fantoma. Ovaj konflikt između svetlosti i tame čini njen lik dubokim i složenim, poput Tamare.

Mina Gligorić u ulozi Kristin u mjuziklu Fantom iz opere i u ulozi Koštane u istoimenoj operi Petra Konjovića.

Fotografije: Željko Jovanović i Dalibor Tonković

Biografija

Mina Gligorić je osnovne i master studije solo pevanja završila na Fakultetu muzičke umetnosti u Beogradu u klasi vanrednog profesora Katarine Jovanović. Ubrzo nakon studija postaje član Opere i teatra Madlenianum debitujući kao Pamina u Mocartovoj operi Čarobna frula. U istoj kući slede uloge i u mjuziklima Jadnici (Fantin, Eponin, Kozet), Poslednjih pet godina (Ketrin Hajat) i operetama Vesela udovica (Hana Glavari, Valensijen) i Pariski život (Gabrijel). U saradnji sa produkcijom iz Kine, debituje kao Cerlina u Mocartovoj operi Don Đovani, a u Pozorištu na Terazijama nastupa u ulozi Kristin, u Veberovom čuvenom mjuziklu Fantom iz opere.

Posebna godina u profesionalnom iskustvu je 2019. godina, gde debituje u 9 solističkih uloga, od kojih se posebno izdvaja uloga Koštane u istoimenoj operi Petra Konjovića, koja je nakon 60 godina od poslednjeg izvođenja premijerno izvedena na sceni Narodnog pozorišta u Beogradu.

Dobitnik je brojnih nagrada, ističe se nagrada za najboljeg mladog izvođača u 2019. godini, koju dodeljuje revija Muzika klasika, a 2021. godine osvojila je treće mesto u vokalnoj disciplini na manifestaciji Armija kulture u Moskvi, kao predstavnik Srbije ispred Ministarstva odbrane, a pod pokroviteljstvom Ministarstva odbrane Ruske Federacije.

Usavršavala se sa istaknutim imenima među kojima su Olga Makarina iz Metropoliten opere, Dejvid Gaulend iz Rojal opere, Vladimir Redkin iz Baljšoj teatra, Marjana Lipovšek i drugi. Neguje i savremeno umetničko stvaralaštvo, bila je i deo projekta koje je organizovala SANU, izvodeći kompozicije srpskih autora širom Srbije.

Bonus video: Šarl Guno, arija Margarete (Faust)